There was something about spring that overwhelmed me somewhat similar to an hourglass with sand slipping rather too quickly through the narrow waist. Too many things I needed to get done seemed to slip through my fingers. The whiplash changes in weather ranging from sunny days promising freshness and rebirth to never-ending downpours making the ground soggy, along with many people close to me coming down with some kind of illness such as the flu (I recently finished recovering from a week-long flu) and pollen-related allergies, were not helping with the spring fever.

For a month, I had been trying to pinpoint a date that six other individuals were available to gather for my dissertation proposal defense meeting. To pinpoint a date within a deluge of countless conferences, different spring break schedules, Easter, and upcoming graduation celebrations, I finally just picked a date and hoped for the best.

The night before the defense meeting while I was working on the handouts and also the table of contents of my dissertation proposal, I received a text message from Dr. Gilchrist.

Hi Sarah – good luck tomorrow. I’ve been looking forward to the proposal meeting. I regret to say, though that I just came down with either a virus or food poisoning. I’m quite sure that I won’t be able to make the trip to Tuscaloosa tomorrow. I’ll send you my comments and I can’t tell you how sorry I am – not to be there to support you.

Immediately, I responded back. Oh dear. I hope you feel better. Food poisoning is no fun. That or a stomach virus. I understand (but sorry to not have you there). Hope Blake and Miss Mave are taking care of you.

After a few more back and forth text messages, I stared at the computer screen for a moment before continuing to work on the handouts. I knew that spring was not a good time of the year to be productive anyway.

The only reason that I taught this spring was to collect data for my dissertation; before this dissertation, I only taught one or maybe two spring terms. I preferred to teach only in the fall—especially with how the attitudes of the students between spring and fall terms were practically polar opposite.

Therefore, I braced myself for the sand to quicken its slippery descent through the spring hourglass. Maybe Newk’s would not deliver the catered boxed lunches on time or that I could not find a good parking spot in time for the meeting? Shrugging to myself, we’ll see tomorrow. I then printed out the handouts and strategically placed them in my book bag.

The next morning, I picked up Alison from her workplace off 459 in Birmingham on my way to Tuscaloosa. I went to the lobby to wait for her. After greeting her with a hug and thanking her for taking leave from work to help me out, I told her as we walked to my Armada that I could not talk much on the way to the meeting in order to not get my throat raw already. My throat always got too raw and my nose tickled when I talked too much and too excited, especially when I was catching up with a friend.

Alison laughingly said okay. Once inside the vehicle, I handed her a copy of the handouts and asked her to prepare for the meeting by reading them.

At one point, I tore my eyes away from the road to ask if Alison understood from reading the handouts. Her eyebrows rose as she shrugged no. Reaching back to the seat behind to retrieve a bound copy of the printed out proposal, I handed it over to her.

“How about if you just flip through this? Perhaps you’ll get a better idea that way?”

Once I got off on the Lurleen B. Wallace exit, my heartbeat sped up as I aimed for University Boulevard several miles ahead. Once we were close to the fraternity row, I spotted a good parking spot and immediately pulled into there against the curb. Glancing at the clock, I left the vehicle running for the air circulation as I turned to face Alison. I inquired if reading some of the proposal did help any. She agreed and said that she could see what I was doing for my dissertation. While I was explaining some things about the proposal, we walked up the sidewalk next to the fraternity row towards Graves Hall.

The conference room 104, the same room as the prospectus meeting back in October, was locked when I tried the knob. Sighing to myself, I looked at Alison while thinking of whom or where to go to ask to have it unlocked. It was already well after 11:30; I had the room reserved at 11:30 a.m.

After finding someone to unlock the door, I anxiously told Alison that I hoped Newk’s delivery would not be too late. Alison encouraged me to go ahead and go to the restroom by saying that she would stay and wait for the delivery. Upon my quick return after washing my hands in the restroom, I was delighted to see the food and drinks already placed on the side table. Alison laughed at the expression on my face.

To my dismay, the bottled water had caps that must be removed with a bottle opener. Not twist off caps. Resigning myself to pour myself some sweet tea, I selected pesto chicken sandwich as my lunch. Just as Alison and I were eating, Dr. Holley and Dr. Major arrived, greeting us with smiles. Dr. Webb came in afterwards. Dr. Major solved the problem of the bottled water by finding a can opener. I decided to keep drinking sweet tea, even though I preferred to have water.

After several minutes of eating and engaging in chatter about pets, children, and busy schedules, I pushed aside my boxed lunch to straighten up my spiral-bound copy of the proposal, handouts, and pens. I noted that Dr. Major had her laptop open, probably with my proposal displayed for her viewing as I noted to her left that Dr. Holley had printed out her own copy. Dr. Webb has his own plethora of papers, some highlighted and handwritten comments marking them.

Dr. Major asked if I was ready to begin. I nodded but excused myself so I could go to the restroom again to freshen up.

Upon my return, Dr. Major asked if there were any documents for the committee to sign. I froze for a moment before sighing. “I knew that I forgot something.” Dr. Major told me that she understood and that it would not be a problem to get to that later.

While I was preparing the handouts last night, I thought about what to talk about. When I noted Dr. Major smiling at me expectantly as to prod me to begin, I hesitated at first. I thought I mentally had a good introduction prepared; however like the last meeting, I felt tongue-tied again and rambled instead. I was too focused on trying not to state the obvious and only discuss what I need to talk about during the meeting, what I would hope to be discussed, what kind of help I needed from the committee.

I could not remember much what I said, except that I asked for their help on tweezing the research questions. I mentioned that Dr. Major prepared me by warning me to not get too attached to these research questions. That I must be willing to be flexible for them to change.

Another thing I remembered saying was that I wanted their input to help make my dissertation more readable and to use my aunt’s word, usable.

I brought up how Dr. Major told me after reading the draft before this version that it badly needed reorganization and that I could reshuffle things around. She felt a sensation of whiplash from reading back and forth between scholarly content and personal memories.

Therefore, I followed her instruction by shoving all the memories from the first chapter into a whole new chapter, the researcher positionality chapter (Chapter IV). After making other changes, I emailed this version to Dr. Major. She approved this version to be shared with the rest of the committee.

I then asked Dr. Major if this version was a big improvement from the last version. She assured me yes, it was definitely an improvement. I nod in acknowledgement, as I felt encouraged. I then decided to stop rambling in my introductory speech by asking for input from the committee.

I experienced a sensation as if I picked up a deck of cards and let them fall onto the table for Dr. Major, Dr. Holley, and Dr. Webb to pick up. I felt uncertain until Dr. Holley smiled at me.

She seemed to sparkle as she animatedly described how she felt like it was not simply reading a dissertation, but more like being there to experience.

She added that she enjoyed reading the proposal, especially the stories. Interesting, she opined.

With such an enthusiastic opening, Dr. Holley’s eyes took on a look of concentration when she shared her concern that while she enjoyed reading it, she still did not understand where I was going with the dissertation.

She wanted me to clarify the purpose of the dissertation. She was not sure due to the way the proposal was structured as it was now. Some things were here and other things were over there, not quite melding together a streamlined purpose for the dissertation.

As she ensued in her concerns over the purpose of my dissertation, I struggled to listen to her while simultaneously think how I could restructure the dissertation for a better reading experience. Then I decided to stop trying to think and only listen to her as she emphasized the need for the dissertation to be better focused in order to be effective.

Then she asked me: “In a short sentence, what is your dissertation about?”

I took a second before plunging, “To explore my teaching experience using writing prompts.” Yet I did not stop there; I kept talking until I realized that Dr. Holley asked for one sentence. I could not remember if I actually clapped a hand over my still-moving mouth to stop talking. But I did remember apologizing that I just remembered that she only asked for one sentence and I gave her a paragraph instead.

Dr. Holley slightly nodded in an understanding way. Comforted by her empathy, I was silent. I waited for her or somebody else to speak. Dr. Holley then inquired about how I would do the conclusion chapter, how I would recommend this study.

She further stated that there are two sides of the story: mine and the students.

Dr. Major followed up on Dr. Holley’s statement by asking me, “What will you do with the student data you’re collecting?”

I responded by explaining that for the data collection chapter, which is Chapter Five, I would do ten vignettes. One vignette for each week I teach. By following Carolyn Ellis’ (2004) Ethnographic I book where she created a composite class in order to explain how she taught autoethnography. I would take all four classes studied to create a composite class to write these ten vignettes showing my teaching experience using writing prompts.

Following each vignette, I would purposefully (I stumbled so badly over saying this word) sample students’ writings, what they wrote in response to the writing prompts in class and also on Blackboard.

Then after each vignette with its set of purposeful sampling of students’ writings, I would write up a reflection to discuss that vignette and the writings.

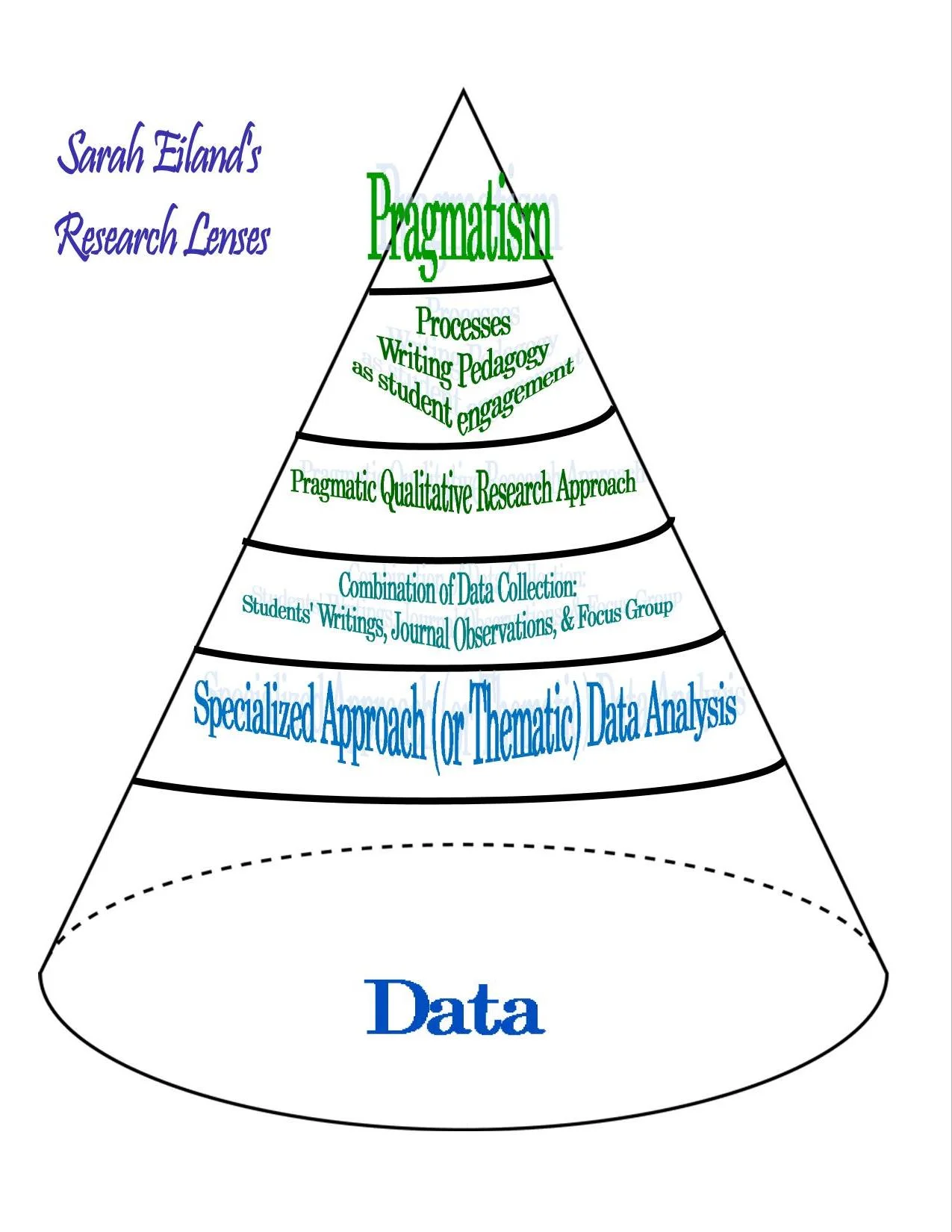

I then explained that the data analysis chapter (Chapter Six), I would use Lee S. Shulman’s (1986, 1987) pedagogical content knowledge to analyze the data. I would discuss each component that make up the PCK (writing prompts as the pedagogical knowledge; knowledge of teaching orientation as content knowledge; students’ prior knowledge and the learning environment as context knowledge).

Dr. Holley commented on how fitting the pedagogical content knowledge as the theoretical framework for my dissertation. She, Dr. Major, and Dr. Webb talked among themselves about some things regarding the use of PCK for my research.

I then glanced in Dr. Webb’s way before sharing my worries about having to refer back to the literature review in the data analysis chapter. I explained that Dr. Webb made me aware of this when I met with him back in September to discuss methodology for my dissertation. I was apprehensive about having to go back and use the literature review to discuss in the data analysis chapter. (Dr. Major much later said that I do not have to go back to lit. review for data analysis).

After listening to my explanation about how I would do the data collection (Ch. 5) and data analysis (Ch. 6) chapters, Dr. Holley said that a person should be able to read Chapter One and Chapter Six (discussion chapter) and know what they will be reading.

Dr. Holley then asked about how I would make recommendations in the final chapter. I let myself to be bogged down in trying to think of ideas that I already jotted in my journal. The ideas that came to me while I was working on the proposal that would be shared in the final chapter as recommendations for future research…I racked my brain trying to remember these good ideas.

Finally, I feebly gave two examples of how I would recommend for future research: one to work with students by having in-depth interviews with them to discuss their perceptions on the writing prompts and the other for how my PCK can be easily applied in any other classroom (any other academic discipline) and not just in Orientation.

As soon as I finished bumbling around trying to share recommendations for future research, Dr. Holley shared her concern that I was spreading myself thin by taking on too much, by asking myself too much. She then suggested how my dissertation can be restructured and to work on the research questions:

Simplify or clarify what the dissertation is about (streamline the research questions on page 14)

Then Dr. Major recommended that:

I restructure the last question by making it more open-ended such as “How might…”

Dr. Webb, Dr. Holley, and Dr. Major then took turns discussing the need to change the research questions, with Dr. Major insisting that there should be just three main questions. These professors seemed to agree with the first and the last questions; they would discuss a potential third question to knock out the remaining questions between the first and last questions. Dr. Webb stated that he would help work on coming up with three research questions.

After moving on from discussing the research questions, the three wanted to talk more about how to restructure the dissertation.

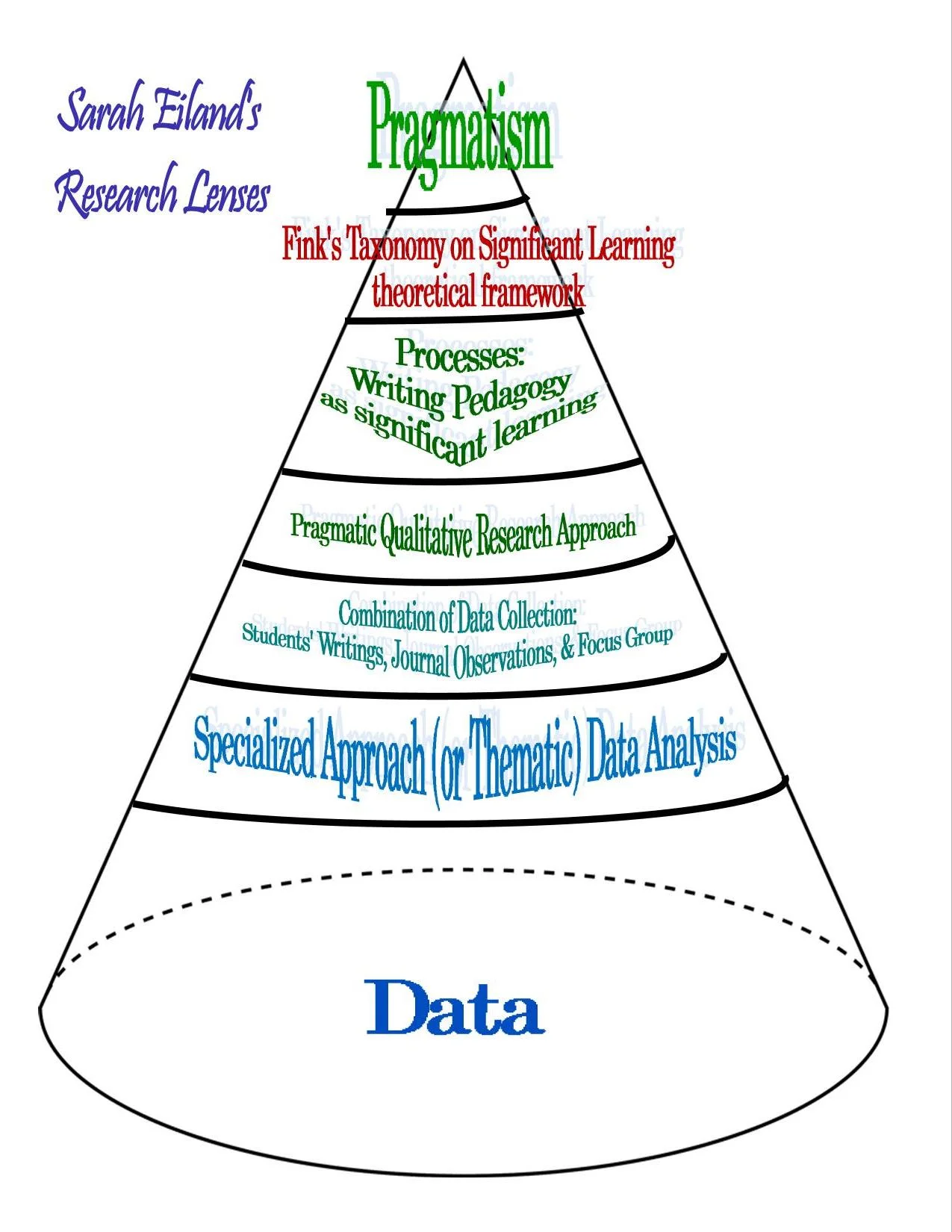

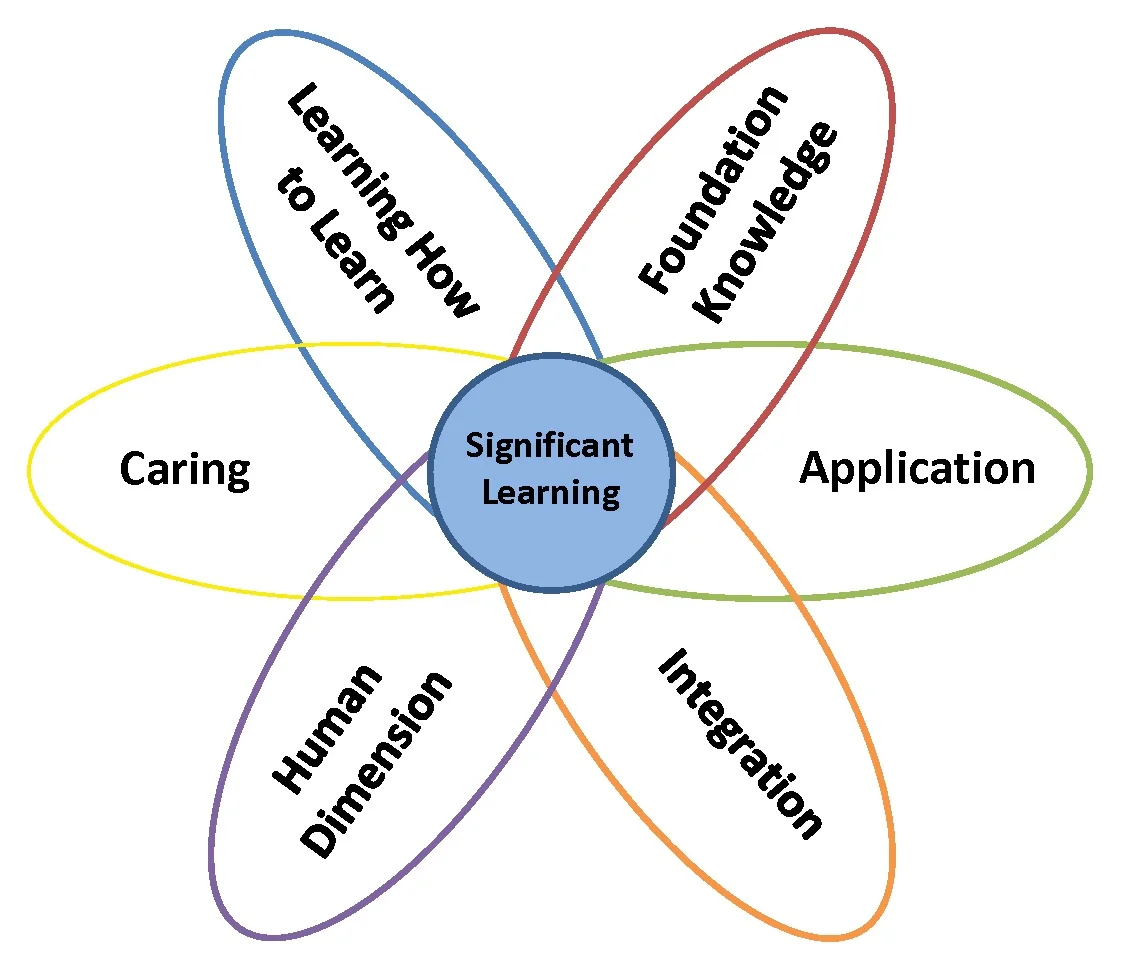

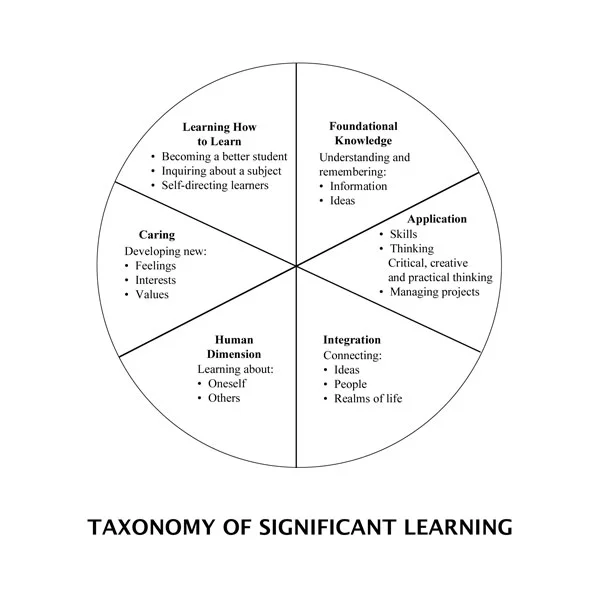

Dr. Webb or Dr. Holley commented on how there were parts that seemed to linger from the older drafts, with Fink’s Taxonomy as example showing up without explanation.

Then Dr. Webb stated that when he was reading specifically Chapter IV (researcher positionality), he got lost in the kaleidoscope.

He went on to say that I needed to try to organize differently. For instance, first explain autoethnography, then explain the method in order to make it easier to follow. There seemed to be parts that need to be in the same place rather than split up in several places.

Dr. Holley gave an analogy of feeling like a pinball, going from one direction to another.

(By the way, I love visual analogies, because obviously I am a visual learner and understand better by following example).

After such input, it was strongly suggested that I go back and create an outline. The outline should help narrow the subject matter, as Dr. Holley insisted because she felt that the subject is too broad.

Reflecting on how willing Dr. Holley, Dr. Major, and Dr. Webb were in giving their input, I realized that I was waking up after feeling so dormant in working with my dissertation. For the past few months, I was working too closely with my dissertation that I was losing focus.

Yet when they brought up the word “outline,” I reacted by muttering loudly that I do not like outlines. I surprised myself for saying that. I saw that as being childish, as I knew and felt the strong willingness in Dr. Major, Dr. Holley, and Dr. Webb to help me improve my dissertation. They were helping me, and I felt secure and grateful in their doing so.

When Dr. Webb firmly remonstrated that it is necessary to do an outline, I studied his face. I recognized this “male” expression he wore as the same one I frequently see on many men, especially my husband, father, and two brothers. It was an expression of “it would be good if you would get to the point”—I then realized that Dr. Webb and Dr. Hardy were the only men to read my dissertation proposal at this point. I then decided that Dr. Webb did bring up necessary, but excellent points throughout the meeting; I did need his guidance to really determine the streamlining of the dissertation.

Dr. Major held up the Dissertation Proposal Table of Contents handout and stated that I could use that and build up on it by adding sentences to each point to help with the restructuring of the dissertation. I then nodded my head, “Yes, a narrative outline. I can see how I can do that.”

Still, I felt uncertain. I looked at Dr. Holley and asked quietly, “How exactly would the outline help me?”

That was when she showed me three different photos in reverse order on her smartphone. She showed me first the systematic placement of bright green post-its before showing me the second of the same bright green post-its placed in a more chaotic way resembling confetti. Then the last picture showed a conference table covered with piles of paper with the bright green post-its tacked on each pile.

Dr. Holley explained that this was a visual of showing the progress of restructuring the dissertation by actually cutting up sections/paragraphs and moving them around to determine the flow. I smiled at her, mentally noting myself to ponder more about this profound visual example later after the meeting when I was alone.

Dr. Major also shared how she would advise some other students to code their dissertations for better organization.

Then she went on and said that while she could see what I was doing with the dissertation, it was not clear. It needed refining. She used the illustration of a sculptor molding the clay into a shape of a head. While the shape was obviously a head, it needs more refining to determine if it is of a male or female, along with distinct features of eyes, nose, and mouth.

Dr. Major’s metaphoric use of sculpting clay into a head to illustrate how an outline helps refine the dissertation emphatically hit the spot.

Reflection on my reaction to the word “outline”

Much later after this meeting, I evaluated why I was aversive to creating an outline, I admitted to myself that I was struggling against myself. Hearing the word “outline” seemed to confront me with the reality that I subconsciously was trying to avoid. What was it about doing an outline for this dissertation that made me feel dread? I did think outlines were useful and that they help clean things up. I usually did not have a problem with outlines. However the thought of creating an outline for my dissertation made me feel anxious.

While I reflected on this anxiety with my personal fitness trainer, Bahia, I came to the startling epiphany that I must have struggled against the idea of creating an outline for my dissertation was because…..I subconsciously knew that by creating the outline would force me to get to the point.

And I have been told frequently to get to the point most of my life. I tended to speak and/or write more to get to the point.

As if Dr. Major could sense my “getting it” after using the head-shaping metaphor, she asked for Alison and me to step out so she could confer with Dr. Holley and Dr. Webb.

During the step-out, I analyzed my badly-timed aversion to creating an outline by talking it over with Alison. At first, she comforted me that it was all a learning process and it was good to have the committee to be understanding and willing to help me.

I then shared an analogy of learning how to perform a forte, a difficult ballet technique. While I did execute other ballet techniques, the forte was one that I could not muster to get past the initial stance. I could not seem to make my body move into a twirling position, with my leg swiveling to extend out before tucking back against my other leg, the supporting leg. I chose to stop before even forcing myself the headache of attempting what was destined to be a failure.

The forte analogy was exactly how I felt about creating an outline. I wanted to stop before even trying, I told Alison.

“Anxiety,” she simply stated. Recalling that she had earned a degree in psychology at Auburn, I stared at her before responding: “What do you mean?”

“Because you are a classic overachiever, you are experiencing anxiety.” Nodding my agreement, I then asked her about what Dr. Major meant about the three questions being “main” questions. Was Dr. Major saying that I have three, instead of one, main questions?

Alison contemplated my question before giving me an analogy of an interior decorator.

“The interior decorator found this beautiful painting with all these gorgeous colors. She wants to make this the focal point of the room. Therefore, she picks out wallpaper, fabrics, carpeting, and furniture that complement the painting.” She paused. “Same way with the main research question and those three questions. The main research question is the painting.”

I then interrupted her. “So the three questions are the sofa, coffee table, and armchair. I can see it now.” I got excited, and then I kept talking. “Now I will have to think about what to put on the sofa such as pillows and blankets and also on the coffee table such as reading material and some candles.” She gently laid a hand on my gesturing hands.

“Sarah, see?” She looked me straight in the eye. “You are worrying about the smaller details. You do not need to worry about what to put on the coffee table. You need to instead focus on how the coffee table relates to the painting.”

As I was absorbing her words, Alison looked over my shoulder and motioned that we were being called back to the conference room. I glanced over to see Dr. Major smiling, waving at us to come on back. She then gave me a thumbs up.

I frowned, still thinking about Alison’s painting as the overarching question metaphor as I neared Dr. Major. Then I realized Dr. Major might have misinterpreted my expression as intended for her. I shook my head as I mumbled something incoherent as to explain that I was just thinking about what I talked with Alison.

As I settled back in my seat, Alison’s revelation about my being a classic overachiever and also how I tended to overwhelm myself by going off on a tangent made me acutely aware of how my students were experiencing specifically writing anxiety. I decided to share with Dr. Major, Dr. Holley, and Dr. Webb the main points Alison and I were discussing during our step-out.

I began describing the forte analogy to share my “sudden” aversion to the word outline. Then I went on to say that I gained better understanding the role of the three questions to the overarching research question.

Alison then explained the interior decorator and the painting as a metaphor for the research questions.

After she finished, I inquired that if I go back and fix the literature review by making sure each theme is pointing to the overarching research question—that I insert “transitional” sentences to ensure relevance of each theme in the literature review to refer back to the research question…..would that be an example of what Dr. Major, Dr. Holley, and Dr. Webb were trying to tell me?

Dr. Major then took on her chairperson stance by stating that my defense passed and that I was to restructure the dissertation by refining and focusing more on the research question, to really tighten the focus.

Regarding the list of my proposed sub-questions, the first question was good, whereas the last question needs to be changed—these would serve as two of my three questions. The committee would work on the third question and send it to me later.

As for doing the vignettes in the data collection chapter, Dr. Major held up her outstretched palm and suggested that I cut down the proposed number of vignettes in half. “Instead of doing ten vignettes, you will do five. Pick five findings that relate to your teaching experience.” I could only sheepishly smile as I scratched notes on my paper while keeping my eyes on Dr. Major as she talked. On my right, Alison was writing longer notes.

In truth, I was relieved when she said five. The tension I was not aware of eased from my shoulders.

Dr. Major’s next recommendation deepened my relief: “You are to keep the dissertation under 300 pages.” A sense of elation and purpose emerged when I nodded in acquiesce.

She ended her recommendations that while Chapter IV (the researcher positionality chapter) was good as it was, I was to follow the dissertation format guidelines for the other chapters.

I then asked if my overall question is too broad. They quickly said no, it was not.

By listening to what they were telling me, I felt really woken up with a whole new barrage of questions. I felt renewed from their feedback. When they were gathering their things, I felt this sudden panic as I realized how time slipped by rather too quickly and I have so many more questions to ask. I checked my phone and was aghast that it was already 1:32 p.m.

I quickly said that due to the difficulty of scheduling this meeting and it being April, I would like to know if early January would not pose any scheduling problems. I planned to schedule my dissertation defense meeting then. Dr. Major, Dr. Holley, and Dr. Webb looked at each other and denied that anything was going on during the first part of January. (Except that Dr. Holley mentioned that she would continue her sabbatical from Fall 2015 to Spring 2016, but she would come to my dissertation defense.)

At my last minute attempt to get more insight from the departing professors, the expression on Dr. Major’s face reflected both understanding and “ready to leave” (she has to leave to have some time to prepare to teach at 2 p.m.); I immediately mentally reminded myself that I could always follow up with more questions through email, text messaging, twittering, or any other wonderful electronic communicating medium.

After the three professors left the conference room, the lingering effect of the meeting reminded me of Dr. Hardy and Dr. Gilchrist. I wondered what and how Dr. Hardy and Dr. Gilchrist would contribute to today’s scholarly conversation. After hearing Dr. Holley’s enthusiastic responses to the storytelling part of my dissertation, along with Dr. Major’s soothing reassurances and Dr. Webb’s honest revelations, I was impressed by the diversity of insightful perspectives regarding my dissertation. While I was sad about Dr. Hardy and Dr. Gilchrist not being able to attend the meeting, I was equally or even more curious about what these two would say.

On 459 back to Birmingham, I spoke out loud the main points discussed during the meeting to make sure that I understood what was expected of me. Alison confirmed what I understood, along with inserting some of her own observations. She reassured me that I was in good shape, because I have plenty to work with. All I needed to do was to really sit down and go through my dissertation, whittle it for refinement. Once I receive the three questions from the committee, these questions would help me focus better and go deeper in my research.

After taking Alison back to her workplace and meeting some of her colleagues, it was apparent that she talked with them about our friendship and what I have accomplished in life because they asked me how the meeting went. The more they asked questions, the more I realized what I should have said to the committee earlier.

One colleague, Scyanne, mentioned that she loved to write, but she was terrible with grammar, punctuation, and all that. I grinned and said that she would love being in my class, because I did not focus on the formal rules of writing. I instead focused on helping students write out their thoughts and ideas onto paper first before worrying about polishing them up. As I was telling this to Scyanne, I jerked and shot a look at Alison, who was leaning against the doorjamb listening to our conversation.

“I should follow my own advice.”

“That is exactly what I am thinking right now.” Alison snickered.

After I left the place where Alison worked, I met up with another close friend, Jane. We went to watch her daughter play softball for Berry Middle against Oak Mountain. Between Haley’s times to bat, I spoke about the meeting and the expectations for me to work on my dissertation. When I mentioned that I was strongly advised to keep my dissertation under three hundred pages, Jane groaned.

“I would not read your dissertation.” She declared. I was not surprised or even hurt to hear her say that, because she was the type who could not sit still for long periods of time. She was always on the go. Plus, she doubled in finance and accounting at Auburn. She was more mathematically-minded.

“Well, I do write a lot.” Narrowing my eyes in contemplation at her, I continued. “I think I write a lot to get to the point. That’s the problem I know I have. I just cannot get to the point right away. I feel like I need to go into a lot of detail in order to clarify things.” Jane then sat up straight.

“This is what Mike taught me,” She raised her hands to illustrate what she was about to say. “First, you tell what you are going to talk about. Then you talk about it. Finally, you tell again what you talked about. That formula helped me make an A on every paper I ever wrote.”

“That sounds too simple.”

“That’s the point. Keep it simple. You do not want to lose the reader.”

Once I let her words sink in, I could see more clearly how I could restructure my dissertation, how I would point each idea/theme/section back to the overarching research question. And, I gained better insight the role of the three main (sub) questions is to help support the overarching research question.

The next day, when I went to my personal fitness trainer’s house for a workout session, I related to her about the meeting. Bahia held many degrees and even started working on her Ph.D. at UAB before making the decision to set aside her schooling in order to dedicate more time for her son. Therefore, her wisdom helped me step outside to look at the progress of my dissertation in a different light.

When I shared with her about my concern about what the committee was telling me, especially what Dr. Webb said, she said that while I certainly wrote in a style that creates anticipation and suspense that was meant for a novel, I was expected to write as to tell right away what I was intending to do.

Then I realized that I probably took on the “show, don’t tell” approach that Dr. Troy, my creative writing professor who taught several of my classes at Auburn, instilled in me, whereas Dr. Webb seemed to want me to do the “tell, then show” approach.

On an ending note to my soliloquy of stating how I felt like I woke up from being so dormant when it came to working on my dissertation, that it was hard to ask myself questions or to critique my own work to improve the dissertation, and that now after having met with the committee, I have this whole barrage of new questions whistling through my mind, Bahia confirmed my feelings by stating that I “need feedback in order to make progress.”